The season of giving is upon us.

Corporate can drives, toy collections, and general Yuletide charity often find their way to the forefront during the holiday months, but this year brings about a renewed sense of need for Windsor’s most at-risk population.

Homelessness itself is not a new challenge for Windsor. “It’s been ongoing. It didn’t just come recently,” explains Brian Yeomans, chair of Windsor’s Downtown Business Improvement Association. “Centralized social services attract people who need those things, and this happens to be downtown.”

Yeomans moved to the city in 1992 and has spent nearly his entire professional life working in downtown Windsor as a business owner; he’s also lived downtown for the past five years. Yeomans is very familiar with the city’s homelessness situation as well as the misconceptions surrounding it. “It’s unfortunate that downtown has been judged as unsafe. These safety concerns are not caused by Windsor’s homeless,” he says.

Originally seen as a problem specific to downtown, homelessness is no longer relegated to Ward 3, having expanded across the city and into surrounding regions, including Tecumseh and Lakeshore. With the Windsor Downtown Mission reporting a count of almost 400 people in 2019, up from 197 in 2017, the city’s homeless population continues to grow quickly.

According to Rev. Ron Dunn, executive director and CEO of Downtown Mission of Windsor, our city’s homelessness challenges are common to cities across North America. Similar concerns have been echoed by other Missions, including those in London and Detroit.

Many other regions share opioid addiction and mental health crises, but what is unique to Windsor is the sudden change in the local housing market.

“With the recent market upswing, your home may have doubled in value, which is great for owners, but not as good for renters who are being edged out by subsequent rent increases,” says Dunn.

“Rental pricing is about 24 to 25 percent higher now than it has been in recent years. You used to be able to get a one bedroom for $600 to $700—now these same units are $950.”

While that increase in average rental price might seem relatively inconsequential compared to other housing markets in Canada, including Toronto and Vancouver, the change is devastating for Windsor’s vulnerable populations.

Ontario’s minimum wage is $14 per hour, which equates to roughly $29,120

annually.

“The challenge is the people who need help with housing are on Ontario Works, which pays $7,878 per year,” Dunn says.

“Adequate housing is just not available for those living on $650 per month.”

Dunn shares that Windsor’s waiting list for affordable housing currently includes 5,000 names, many of which represent an entire family in Windsor-Essex country. There are effectively 15,000 people waiting for a place to call their own.

The financial realities for many of Windsor’s services that are oriented towards the homeless are difficult. The Downtown Mission of Windsor is the largest shelter from Windsor to Toronto, but receives no government funding.

The challenge, Dunn says, is that government needs to take homelessness, mental health, and addiction concerns more seriously.

He adds that animal shelters in Canada currently receive more public funding than those helping people experiencing homelessness. “If this were SARS, this would be funded, but people feel as though mental health is something we bring upon ourselves. This is a public health issue and needs to be treated as such.“

Sandra and Tweets, two Windsorites experiencing homelessness, shared their own experiences from living on the streets of downtown. They were frank in painting the realities of surviving Windsor’s winter months. Between ensuring their cold-weather clothing wasn’t stolen from them and the ongoing challenge of finding public places to stay warm, they say libraries and public bathrooms are often the only places they could seek sanctuary.

Tweets says that one of the greatest challenges for those living on the streets is the lack of activity and safe spaces for people like her, and how this inactivity and lack of stimulation spurs drug use among homeless populations. “It’s a nightmare living out here. We’re not allowed inside the Mission until around 7 p.m., so many people spend the day on their own with nothing to do. That’s when people start using. This only gets worse as it gets cold and everyone tries to stay warm.”

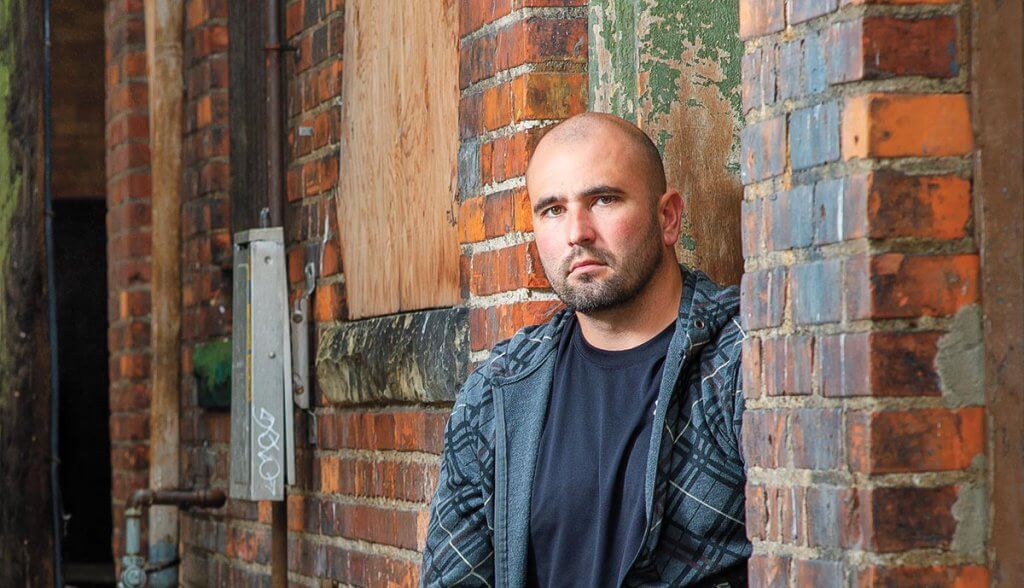

Greg Lemay, a Windsor community activist and advocate for the homeless, gained notoriety after spending 36 hours on the streets of Windsor during the summer of 2018, followed by another 48 hours in November 2018. His experiences also highlighted the dichotomy between the realities of what causes homelessness and what many of us assume to be the source.

Through interviewing upwards of 90 people living on the streets, he found that surprisingly few homeless people start out with addiction issues, but the intensity and difficulty of the experience is enough to make addicts out of most people.

“I’ve never touched a drug in my life, but another 48 hours on the streets might have broken me. It was that hard. I knew I was going home, I knew I had a family, and I knew my experience would end Sunday at 5 p.m. I can’t imagine what it might be like for someone with nothing to go back to.”

Despite knowing the downtown area well, Lemay was emphatic that experiencing homelessness in a city that we’re familiar with is still a wholly unfamiliar experience for those new to the streets. “I went out there not knowing what to anticipate. You know, you don’t think about these things. Windsor is a city I grew up in and feel safe in, but when it came time to go to bed, it became a different world,” says Lemay. “You don’t feel safe. You want to go to bed but even in a city you know you can’t find a spot to put your head down. All I could think was, ‘Do I want people to see me on this corner?’”

The holidays come with an important brand of good cheer for Windsor’s shelters and not-for-profits serving the homeless—the season of giving is an essential source of funding for Windsor’s Downtown Mission.

Dunn shares that this time of year is typically what generates the funds that support the Mission year-round, and are essential to keeping the lights on. “The Mission is 94 percent publicly funded, and from non-sustainable sources. Eighty percent of donations are people sending $50 to $100 per year, and 60 percent of our funding comes in at Thanksgiving and Christmas.”

When asked about funding and cash flow throughout the rest of the year, Dunn’s answer was sobering. “Come July and August, we’re scraping the bottom of the barrel. We’re thankful for any and all contributions given to us by the community, but we need more help. This isn’t just a holiday problem. We need people to care all year long.”

Many experiencing homelessness are attracted to Windsor’s milder climate, coming from away during the winter months. This influx of people further strains Windsor’s already burdened shelters, but winter’s weather makes it all the more important for homeless individuals to secure a bed.

Greg Lemay’s 48 hours spent outside in late 2018 proved to him first hand that homelessness in winter presented a new set of challenges.

“I was always wet, and I was always cold. I woke up to water on my face the second night I was out, and it was because it had started snowing.“

This year, Lemay and Dunn jointly organized a 24-hour bench talk outside of the Downtown Mission of Windsor.

From 11 a.m. on November 14 to 11 a.m. on November 15, Dunn spent a day without food or drink in support of Windsor’s homeless. The event, Lemay says, allowed the community to visit with Dunn, to discuss the state of homelessness and the Mission’s operations, and to contribute much-needed donations to support the cause. The chill felt from the late-autumn season hinted at the coming winter that will impact so many of those experiencing homelessness.

‘The cold weather brings about serious health risks for Windsor’s vulnerable homeless population,” says Rita Taillefer, a nurse of over 30 years and executive director of the Windsor Essex Community Health Centre, the organization behind Windsor’s new mobile health unit. “Frostbite becomes a major concern, which is why it’s so important to ensure that we’re able to deliver care to homeless populations in their own environment, to treat things like this.”

Taillefer and WECHC plan to do this through the mobile health unit, a recent addition to their existing six brick-and-mortar locations in Windsor-Essex County. The mobile unit will service those having trouble coming to their centres, including their downtown Street Health location, which that serves predominantly vulnerable clientele like Windsor’s homeless.

The unit’s purpose is to go where people need them most and deliver on-the-spot care. “Whether it be flu shots, wound care, or general health support, a primary care practitioner will be on board to help with medical needs, and help in a way that’s familiar and non-threatening since we have a team of people that the population have been working with for years,” Taillefer says.

The mobile health unit will operate as a medical complement to Windsor’s existing Mobile Outreach and Support Team (MOST), an initiative supporting those on Windsor’s west side and downtown with housing and health challenges. The MOST team is made up of a driver trained to support those with physical disabilities, a social worker, and outreach worker. Throughout the winter, MOST is an essential service, delivering cold-weather clothing like mittens and socks to those on the street.

“While many of our client base miss those they’ve been separated from around the holidays, the biggest threat here is the cold,” Taillefer says.

So, how can the average person help Windsor’s homeless populations this holiday season and beyond? “Time, talent, or treasure,” says Dunn. “Remember, the number one users of food banks are kids. Buy an extra box of cereal or two cans of tuna at the checkout. The Mission is made up of a lot of people doing a little bit.”

Lemay echoes the sentiment. “Have something extra? Blankets? A case of water? Socks? Bring them downtown. Three dollars and 11 cents provides a meal at the Mission—why not just contribute that instead of buying a specialty coffee one day? It would mean the world to someone who needs that meal.”

Being treated with humanity goes a long way, asserts Yeomans.

“Start a conversation and try saying ‘hi.’ The stigma against the homeless is real, but there are a lot of people in a very unfortunate place through no fault of their own, after the downturn of the economy in 2008. Most people don’t want to be homeless. There is a zero percent vacancy rate in Windsor, and not a lot of people can afford rent. Look beyond where they live. “

Taillefer reminds us that we’re not immune to the struggles felt by Windsor’s homeless, and to be kind.

“People come downtown and see addiction and homelessness and think that it’s beneath them. We need to change the narrative that homelessness needs to be pushed aside and ignored,” she says.

“It could happen to anyone, including your family. We could all use more compassion.”