The Walker Power building at Devonshire and Riverside, once a virtual ruin, had nevertheless become a favoured backdrop for wedding engagement photos. When Piero Aleo and then-fiancé Laura posed at the Power building in 2015, he barely noticed it.

Returning from his honeymoon, Aleo received a phone call from friend Stephen Ducharme that would change the course of his life.

“Remember that rundown building with the ivy in Walkerville where you posed for your engagement photos?” Ducharme asked. “It’s for sale and we should take a look at it.”

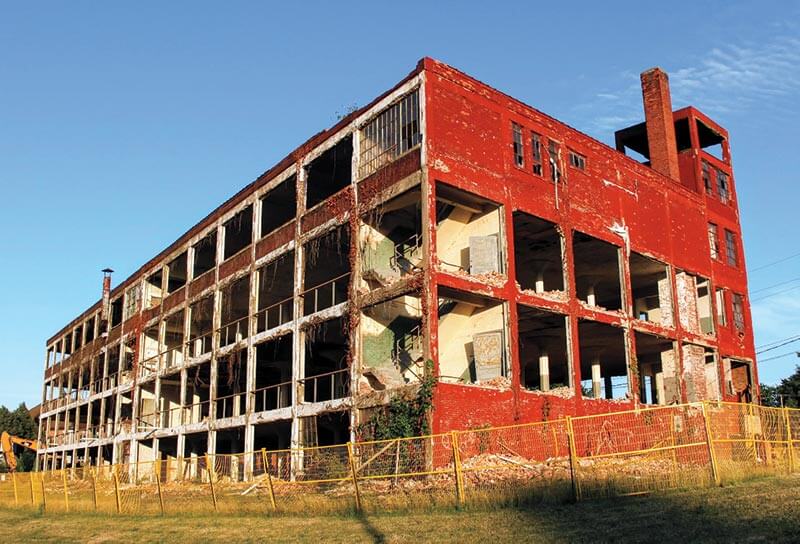

After only a brief walkthrough, Aleo was smitten: “I recognized it wasn’t a teardown despite its rough-looking exterior—broken windows and frames, missing brick, exposed concrete, rebar poking out, ivy-covered windows. I’m an engineer, and was impressed with its solid bones. I work with concrete structures for a living. I immediately understood what it would take to restore this building. I said, ‘Let’s buy it.’ What I didn’t know at the time was its remarkable history.”

As Aleo discovered, heritage buildings reveal themselves through their stories and connect us to our past. They exist as a tribute to a specific time in our history, representing continuity with our past, worthy of preservation for their aesthetic and historical value.

And a very few, like the Walker Power Building, are remarkable achievements designed by influential architects.

Aleo and Ducharme formed a family partnership with their fathers, engineer Vincent Aleo and famed Windsor lawyer Patrick Ducharme; they purchased the property for $900,000. Discovering no one would finance a property without tenants, the group capitalized the renovation project, which was funded by the engineering team of Aleo Associates Inc. and legal firm of Patrick Ducharme.

“I oversaw 100 percent of this project,” said Aleo. “The partners provided funding and support when needed. Our company does development for a living; we were excited to take on this huge challenge.”

“The first step in the renovation was to clear the debris inside the building, over 600,000 lbs of junk!” said Aleo. “We took our time early on as we had to rip out the entire main floor and remove many layers to get to its bones.”

Aleo began to look into this building’s past. “I spent a lot of time doing research to understand its story.” He learned that in 1910, Walkerville was booming, and had been the site of the birth of the Canadian automobile industry: Ford, Packard, Studebaker, Chrysler, and many others lost to the sands of time had located their start-ups in Walkerville.

Also at the time, Hiram Walker’s sons—Edward Chandler, Franklin Hiram, and James Harrington—had undertaken construction of a commercial/industrial complex directly north of the Lake Erie & Detroit Railroad Station at Devonshire and what was then Sandwich Road (now Riverside Drive); the three sons were actively expanding their father’s company town (Walkerville’s benevolent dictator Hiram Walker died in 1899).

Conventional 19th-century brickwork mill factories were poorly suited to 20th-century manufacturing requirements, particularly for a rapidly expanding automotive industry. Support beams and walls impeded car assembly, limiting the number of windows providing natural lighting and ventilation. Wood floors were ill-equipped to support heavy machinery load requirements, soaked up oil and other lubricants, and were fire hazards (many auto brickwork factories were destroyed by fire).

Architect Albert Kahn and his brother engineer, Julius, began experimenting with embedding steel rods in concrete, and determined these were ideally suited for car factories: they were cheap, strong, flexible, fireproof, able to absorb equipment vibrations, and their superior strength allowed greater spans between columns, resulting in larger windows to bring in light, air, and dignity to the workplace.

In 1903, the Kahn Brothers proved the viability of their system with the construction of Henry Joy’s Detroit Packard #10 on Grand Boulevard in Detroit. This breakthrough changed the manner in which all industrial buildings were built going forward, becoming the gold standard for all factories—one of the most important, yet often overlooked architectural advances of the early 20th century.

Detroit-based J.E. Kinsey designed the Walker Building’s plans (he was working nearby for Ford of Canada); the Walker Power Building officially opened September 1, 1911 with three floors encompassing 21,000 square feet. The first offices were for the Walkerville Light and Power, owned by the Walkers (like almost everything else in Walkerville); the name stuck to the building.

The building quickly filled with tenants; a four-storey 32,000-square-foot addition was added in early 1913, and featured a freight elevator. In 1918, a fourth floor was added to the original section, bringing the structure to 60,000 square feet.

Aleo discovered the Power Building’s second phase incorporated an even more advanced construction method. In 1909, C.A.P. Turner developed a concrete system using four-way flat-plate slabs and mushroom columns. Around each column, the slab was reinforced with capital in the shape of an inverted cone, which resulted in the requirement of fewer beams and joists, allowing simpler mechanical and electrical installations; also, thinner slabs required less concrete. Since there was no need to erect formwork for the beams, construction was accelerated and labor reduced. This hybrid of the Kahn method became the standard for modern factories until around 1920.

Remarkably, the Walker Power Building was one of the first in Canada to incorporate both pioneering methods of concrete construction.

Another complex, the Peabody Building, rose west of the Power Building. Although separate, the two structures seemed connected when a second wing was added to the Peabody Building tight against the Walker Power Building, giving the impression of one large complex. Sadly, the Peabody Building was demolished in 1985 by the City of Windsor.

When the Walker Power Building’s renovation began in 2017, the site unveiled another secret: it was built atop an abandoned railroad turntable. In that era of steam locomotives, railways needed a way to turn the locomotives around for return trips.

Hiram Walker’s Lake Erie & Detroit Railroad built the turntable, but it never functioned properly and often broke down. Taken out of commission in 1895, it was buried and forgotten. Remarkably, the Power Building’s architects tied the structure’s foundation into the turntable.

“After we uncovered it, we were required to hire a full-time archeologist on site to monitor work progress,” said Aleo. “The suggestion was to bury the turntable but I wanted to preserve and showcase it under glass, to be able to walk over it. There is an ongoing approval process, but we are optimistic about its long-term preservation.”

Aleo also travelled to Chicago and New York for inspiration. One site he visited in Chicago motivated Aleo to add a 7,000-square-foot fifth floor in 2019, which includes a meeting room/lounge, terrace, and patio area with one of the best 360-degree views in the city.

The partners have moved into the finished building, “our reward for facing all challenges. It has been a tremendous opportunity despite inherent risks. This is a project that could have easily bankrupted us.”

In his dealings with the city, Aleo also discovered local development standards create numerous challenges. “Mayor Dilkens helped us tremendously; he was able to facilitate and find solutions to our roadblocks and problems.”

“The project has finally come to fruition. The Walker Power Building is ultra-modern, meeting all modern codes without compromise. We feel like we went above and beyond what we saw in other restoration projects. We have tremendous interest in the building and we anticipate being fully leased very soon.”

“Everyone who has moved into the building tells us the same thing: ‘We just love coming to work here. It is such a phenomenal space.’ Modern designers don’t construct buildings with the integrity of these old structures. Today, decisions made regarding cost-savings. I now have a tremendous appreciation of the quality that once went into buildings; the craftsmanship is tough to replicate.”

Aleo offers one final piece of advice for anyone considering a renovation project: “Don’t give up! There’s a solution to every problem—it’s inherent in the engineering profession.”