Surrounded by people you’ve known since you were five years old, lost in your troubled thoughts, you have a secret you can’t trust with even your closest friends. You lose sleep over it and your thoughts are constantly spinning. If you tell them the truth, will they still be your friends or will you be shunned by the people you thought you could trust?

For the thousands of LGBTQ athletes across Canada, this nightmare is real.

Sports like hockey, football, and baseball have been built around years of tradition where there is a fear of changing dynamics—that any subtle tweak to the status quo may upend the perceived fragile balance that makes a sport “great.”

Brock McGillis grew up in Coniston, a hamlet now a part of the City of Greater Sudbury.

“When I was six years old, my parents were watching a movie and there was a gay character and I asked, ‘What if I’m gay?’” he recalls. “They said, ‘If you’re gay, you’re gay.’ I suppressed it and hid it for a very long time. Through my teens, I had more realizations as I hit puberty, but I suppressed a lot of it.”

McGillis grew to love hockey and soon excelled as a goaltender. He found his way to the Ontario Hockey League, where he played stints with the Windsor Spitfires and Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds. But behind the scenes, something was wrong.

“I became very depressed; I was suicidal,” he explains. “From the ages of 18 to 23, I drank every day.

“There was such a fear [of discovery] that I took it to the extreme and became a stereotype of a hockey player. I became the hyper-masculine hockey bro who was a womanizer and cocky.”

The stress and abuse took its toll. McGillis, still a solid goalie, wasn’t sleeping. Throughout this time he had a string of injuries and severe depression that hampered his career and ultimately ended it.

At 23 years old, he finally came out to his family.

Growing up in the tiny border town of Carnduff, Saskatchewan, Hayley Douglas felt like she had something to hide.

She played hockey with the boys in her hometown until she was 14, then moved north to Melville to play girls’ AAA. During her final years in Carnduff, she found herself chasing boys, but she was actually interested in a girl in her class.

At 17, she moved to Edmonton to attend the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology and played university hockey with the NAIT Ooks. After secretly dating another girl at the school for four months, she felt it was time to tell her sister and mother.

“I told my sister—she wasn’t all okay with it, so I didn’t really have a great conversation with her, and I was pretty upset so I called my mom right after,” she explains.

She told her mother the truth. “[The phone] went silent and instantly I could tell it wasn’t going to be the best reaction I thought I was going to get.” She said her mother hung up on her and she didn’t talk to either of them for months.

Her teammates were more welcoming.

One night, after a skate, she came out to the whole team. “I was just scared that they would think I was looking at them in the dressing room or that I would try to hit on them or something but that’s the last thing I wanted because your team is your family,” she says. Douglas said they weren’t shocked. They were mostly supportive and she was happy to get a few hugs from her teammates that night.

When she told her hockey coach, Deanna Iwanicka, the advice she received was to be true to herself. “I’ve never forgotten about that,” says Douglas. “That’s probably the best reaction I could have asked for.”

Last year, she came out to both sides of her family and found it to be a mixed bag. “They’ve all gotten better and they don’t say anything about it,” she says. “It’s the unspoken truth, I like to say.”

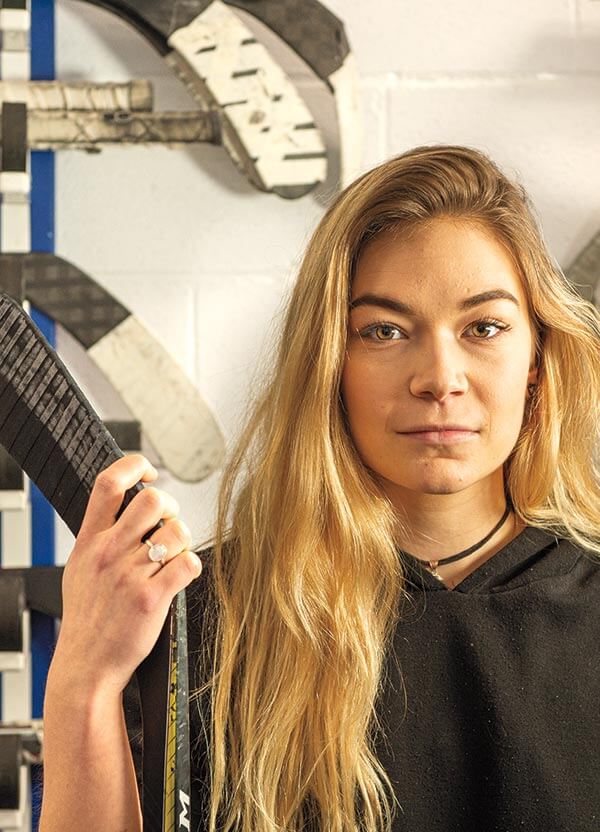

Douglas, now 22, studies Kinesiology at the University of Windsor and is recovering from knee surgery while she trains with Iwanicka and her new team – the Lancers.

In 2014, the Ontario Human Rights Commission ruled in favour of Jesse Thompson, a transgender hockey player from Oshawa who was outed to his teammates by his coach, allowing him the right to change in the dressing room that matched his gender identity. Soon after, minor hockey associations were mandated to make their coaches and volunteers take a course on gender identity, coming out, and a coach’s role if a child comes looking for guidance.

Mostly by coincidence, the Windsor Minor Hockey Association created a program around the same time that is unique in local hockey and could be beneficial going forward.

“The THINK program is a WMHA initiative that was created as a result of an insensitive comment made by a WMHA board member,” says WMHA abuse and harassment advisor Frank Providenti, a superintendent with the Windsor Police Service. “THINK [True, Helpful, Important, Necessary, Kind] was created to communicate to all members of the WMHA on how to communicate with each other in a respectful manner.”

The WMHA keeps a yellow THINK triangle on each of their jerseys and features it at the top of their website’s main page where members can follow a link to access the program’s resources.

“As members of the WMHA, we must THINK about our actions when we text, talk, and type,” says Providenti. “As players, parents, and volunteers, we must realize that our words may be inappropriate, insensitive, or interpreted in a way that is hurtful and demeaning. We need to THINK before we convey our message.”

Providenti also explained that all team officials are required to take the Ontario Hockey Federation’s Gender Identity and Expression Course and are required to pass on that knowledge to their players and parents to create a safe and inclusive environment.

“This message can be conveyed by a pre-season chat and throughout the year as required.”

Brock McGillis, 35, is now a public speaker on LGBTQ rights. He feels that the course isn’t being taken seriously by coaches.

“I think you have to get coaches who want to be inclusive—a lot of coaches don’t want to be,” he says. “They don’t want to deal with this at all.

“We need to help coaches and parents see and the importance of it and the need for it. I think we need to humanize the issue and that’s something that I’ve been doing by going around and getting people to say, ‘Okay, this matters.’”

Providenti contests that the modules are helpful by the fact that before this, gender discrimination based on identity and expression was never openly discussed and now is.

“This training has allowed us to have an open dialogue about real issues that our children deal with on a daily basis,” says Providenti.

He does concede that there needs to be a better way of confirming that the “pre-season chats” occur. “The OHF expects that these meetings are implemented into the existing procedures for teams at the beginning of each hockey season and will undertake a random audit to ensure compliance with this requirement.”

In girls’ hockey, the Sun Parlour Female Hockey Association is not required by the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association to make coaches watch the modules. “We go by what the mandate is for the OWHA, which is zero tolerance for any bullying, harassment, hazing, that sort of thing,” says SPFHA president Dawn Hoster.

She explained that harassment complaints of any nature are pretty rare in the SPFHA but they have mandated protocols for dealing with such incidents that can lead to warnings, suspensions, and even expulsions. “We want to make sure whoever comes to our organization feels that they’re in a safe place where they’re included in everything that goes on, they’re not going to be harassed, they’re not going to be made fun of, they’re safe and can learn and can enjoy the sport.”

Hayley Douglas thinks that positive messaging such as posters and stickers in dressing rooms may help create a change of attitude, more awareness, and a more welcoming environment. She added that the screening process for coaches could benefit from a requirement for coaches to have gay-inclusive attitudes.

As well, Providenti believes that education is the key to changing our attitudes and beliefs. “The earlier we can teach our players and parents about the ramifications of bullying and harassment, the more success we will have in providing a safe environment for our players.

“The more we talk about gender inclusiveness, the more we can provide all kids with the opportunity to feel welcome, included, and thrive.

“Consistent leadership and mentorship within the WMHA are crucial because the message has to be sent that we as parents, players, and volunteers will not stand by idly while people are excluded.”