Maybe “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” but as we all know from Shakespeare’s play, a name also carries a lot of weight. A name can cause feuds among families, it’s what some choose to accept or reject upon marriage, and on a local level, names feature on street signs throughout Windsor.

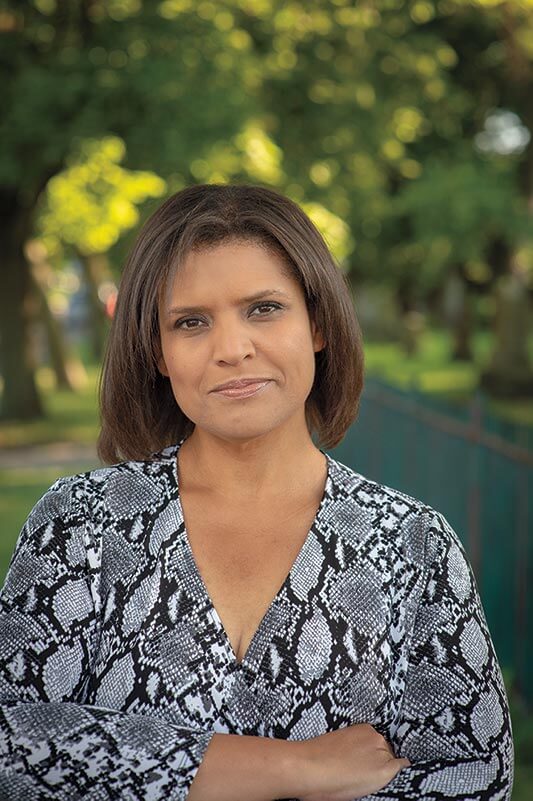

Local educator and president of the Essex County Black Historical Research Society, Irene Moore Davis, says that we need to take a deeper look at our streets and ask ourselves who they’re named after, what they’ve actually contributed to our region, and who we’re failing to represent?

Baby, Marquis, Russell, and Peter are all “Windsor Famous” names when learning about local history, but there are missing pieces. Most people living on or driving by these streets wouldn’t know that they’re named after slave owners.

“I want people to be conscious of it and understand that our history here is complicated,” Irene says, feeling especially haunted by these street names. Russell Street and Peter Street are named after Peter Russell, a slave owner who wasn’t from Windsor but was actually from York (Toronto) and came to this area, bought plots of land around Sandwich, and split it and divided it between United Empire Loyalists. After that, he decided to name the streets after himself. “I don’t think we should just honour people who have accumulated a lot of wealth and power. Those aren’t always the values to uphold.”

Irene adds that we need to learn the full scope of our local history, that our city’s wealth was built on the backs of Black and Indigenous peoples. “Thinking about early pioneers that we call founding families and their involvement in the fur trade, who was doing the heavy lifting?” she asks. When you look around, you don’t see their names—or many non-white or non-male names—on important plaques or streets.

Local activist Philippa Von Ziegenweidt has also noticed the lack of diversity when it comes to our street names and has designed a map that displays 88 male-named schools, libraries, and streets, with only eight female names. She first started examining this when her daughter was 12. “When kids are thinking about their career choices, it’s important to look at role models. If these role models all fit a certain demographic, then what you’re telling your children is ‘here are all of your limited options.’”

Philippa adds that it’s not enough to simply have a female name like Henrietta Street, because it’s not aspirational. Take Adie Knox, for example: most of us know this recreational centre but when you look into the name, Knox was memorialized for being the wife of the male editor of the Windsor Star, W.F. Herman. Meanwhile, they could have named the centre after Ellen van Wageningen, the paper’s first female editor-in-chief.

“It’s not to say these named men weren’t worthy but look at all of these women in yellow [on the sidelines of the map]. You can’t say we don’t have great women—both dead and alive—as well.”

This goes beyond naming, as we need to go further and tell the whole story. Matthew Nahdee, executive director at CAIFC (Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre) brings up Wyandotte Street, which, despite sounding French, is actually a nearly extinct Indigenous tribe from the area (Wendat or Wyandot).

“We have more Native words in Windsor than you’d think, but they don’t bring up the right feelings or history. We don’t realize that they’ve been amalgamated and now assimilated into Windsor-Essex,” he adds. Even though these Indigenous names exist in our city, they’ve been whitewashed and turned into “easier to pronounce” versions like Ojibway (Ojibwe) or Mic Mac (Mi’kmaq), so the original meaning and intention has been lost.

Unintentional ignorance or lack of education can no longer be an excuse as more resources are available to educate ourselves about the past. Names that exploit slavery or mistreatment of races continue to be harmful to past and current generations who deserve to see themselves represented in their city. “We need to make it possible for kids of racialized backgrounds, those growing up as LGBTQ, FNMI, and frankly just girls to be able to look around the landscape and see their identities reflected,” Irene says.

We shouldn’t just change the street names, Irene says, because that would eliminate the learning opportunity. Irene, Philippa, and Matt all agree that creating an interactive educational plan through the city and through schools, along with naming new landscapes after the missing parts of our history, will help to tell Windsor’s full truth—both the good and the bad.