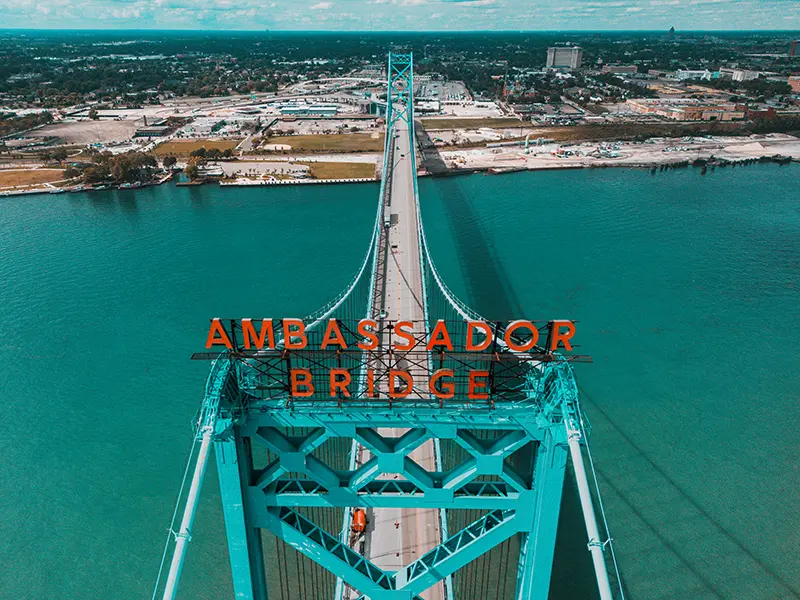

Paris has the Eiffel Tower. Athens has the Parthenon. Windsor has the Ambassador Bridge.

Few cities possess a single iconic structure that embodies its identity. The majestic expanse of the Ambassador Bridge says all anyone needs to know about Windsor: We build things here—big things, things that stand the test of time.

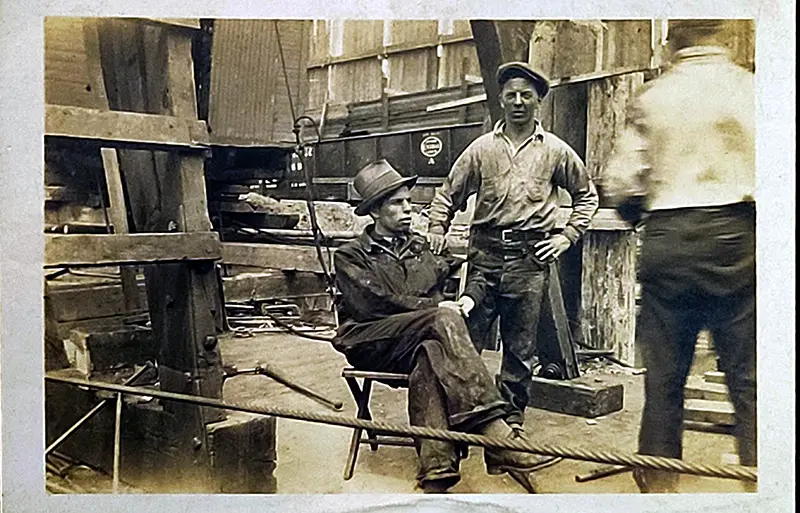

The city is doing it, yet again, almost a hundred years later with the Gordie Howe International Bridge. As the people of Windsor go about their lives, the multi-billion-dollar construction project progresses inexorably toward completion on the western bank of the Detroit River. More than 8,500 individuals have worked in one form or another on the new international bridge. More than forty percent of those people are from this area: ironworkers, operating engineers, carpenters, millwrights, bricklayers, cement masons, electricians, plumbers and labourers. At the zenith of its construction, the $23 million Ambassador Bridge project, 1927-1929, had more than 600 labourers working on the site.

This is not history repeating. This is the face of a city whose forge of industry and innovation has never cooled.

Following the horror and trauma of World War I, 1920s North America was a time of great optimism, dynamism, and a renewed belief in human ingenuity. That sense was no more evident than in Windsor, Ontario during the later years of the decade, where two colossal projects were undertaken virtually simultaneously: the construction of the Detroit-Windsor tunnel and construction of the Ambassador Bridge.

Supporters of the bridge project were matched by those who felt a tunnel was the better option to connect Windsor and Detroit. The October 3, 1925, Border Cities’ Star ran a front-page article stating: “The controversy as to whether a tunnel or bridge would be the better means of overcoming the transportation difficulties of the Detroit River is over half a century old. It is not by any means a new issue.”

A third idea was published in the November 14, 1925, edition of the newspaper: “Plans to connect the Border Cities with Detroit by subways, rather than a bridge, offer the best solution of the cross-river traffic problem, F.G. Engholm, of Toronto, engineer for the Detroit Subways Company…” The article was accompanied by futuristic depictions of Windsor’s waterfront, entirely paved, filled with subway cars and boxy terminal buildings. Not a tree to be seen!

Most municipalities—then and now—faced with choosing between massive projects would spend years studying, stalling, debating, deferring before choosing one of the two options. The 1920s was a time of bold action, and the leaders in Windsor and Detroit chose to build both a bridge and a tunnel. Construction of the Detroit–Windsor tunnel began in the summer of 1928 and was completed in November 1930. Construction of the Ambassador Bridge began on August 16, 1927, and the bridge opened for use on November 15, 1929, less than a month after the catastrophic stock market crash that precipitated the Great Depression.

Private enterprise had the most to gain from the span, so investment from the business community—locally, and reaching all the way to New York City—was incorporated as the Detroit International Bridge Corporation. This would come back to haunt the bridge half a century later, in 1979, when Detroit billionaire Matty Maroun purchased the bridge company.

“The only way things can be done today,” proclaimed Henry Ford, one of the project’s backers, “is by private business.”

The Ambassador Bridge’s origin story begins in the mid-1920s when New York businessman, John W. Austin, approached financier Joseph A. Bower—who had lived for twenty years in Detroit earlier in his career—about reviving previously abandoned plans for building a bridge across the river. The 1920s was certainly a dynamic time—from that meeting between John Austin and Joseph Bower, a $23.5 million privately financed link between Detroit and Windsor was born.

Few aspects of the bridge’s construction were easy after that point. The feat of raising sufficient funding was almost negated when a Toronto financier who was “hired to sell its securities instead stole the money, ran off and ultimately committed suicide in a jail cell after being convicted of murdering a drugstore clerk…” according to a May 21, 2015, MacLean’s Magazine article.

Then, like now, the bridge’s construction created a “knock-on effect:” not only was the immediate location affected by the project, but roads throughout the City of Windsor, leading to the bridge, required upgrading to handle the anticipated increase in traffic to the new crossing. This is a scene currently being replayed around the construction of the Gordie Howe International Bridge.

Interestingly enough, the bridge that was planned in the 1920s is not the one that was ultimately built.

“The original bridge design called for a much larger structure,” says Windsor historian, Pat Brode. “The original design was going to be a huge, brick structure—a train bridge. In the 1920s, people couldn’t wrap their heads around the idea of motorists driving across the bridge in cars. They imagined people would only cross in trains and buses. The original entrance to the bridge area would have been at Tecumseh Road, rather than at Wyandotte Street.”

As with all grand plans, the original designs for the bridge evolved and the notion of automobile traffic across the span was embraced. Nearly a century later, in the science fiction year of 2024, Windsor residents are once again witnessing what their sepia-toned forebears beheld: a massive structure slowly coming together over the Detroit River.

Incredibly, by March 1929, the Ambassador Bridge project was fourteen months ahead of schedule. By that time, the cables were all in place and the main span was being built. Later that month, however, while Joseph Bower attended a dinner to celebrate his accomplishment with the bridge, a pair of engineers took him aside and informed him that the heat-treated, high-carbon steel wire used in the bridge’s cables was defective. One can only imagine the look on Joseph Bower’s face upon hearing that news. Pat Brode captured the moment in his book Border Cities Powerhouse, writing: “As Bower later recalled: ‘The whole thing had to be torn down and replaced… I didn’t want any more food that night nor wine either.’”

The December 11, 1993, edition of The Windsor Star recalled: “Within days the suspended roadway was removed, along with the suspending cables and the main cables cut into thirty-foot sections. By June, with the dismantling completed, new cables were spun, using traditional cold-drawn wire.”

Carefully, gingerly, meticulously, painstakingly, the cables were replaced. No textbook existed to guide the process. The engineers and iron workers on the project just figured it out. Following this setback, progress resumed.

The Ambassador Bridge was dedicated on November 11, 1929, and the event came off in true Windsor form. As politicians and representatives from the business community squared up to speechify to the fifty thousand people gathered on the Canadian side of the bridge, the crowds took matters into their own hands, breaking through the rope barriers and pouring onto the bridge. Some daring souls even climbed the catwalks to the top of the piers. It was the most massive structure those citizens had ever seen in their lives, and they sought to experience it firsthand, viewing the river from its great height. The newspaper of the day stated: “No ceremony could have been half so impressive as the unbridled, uncontrollable rush of thousands of people, turning out to see this new engineering marvel of the world.”

Today, the Goliath structure of the Gordie Howe International Bridge looms over the west Windsor landscape.

Local media recently reported that the support tower on the Canadian side of the Gordie Howe International Bridge now stands at its full height: a dizzying 722 feet (220 meters). Its counterpart on the U.S. side reached its full height in August.

Heather Grondin, vice-president for the Windsor Detroit Bridge Authority (WDBA) explained: “The towers are significant. They hold the weight of the bridge, not just the bridge itself, but also the future traffic and they hold the cables that attach from the road deck to the towers themselves. People can really start recognizing what the cable stay bridge design means for the skyline.”

“Schedule,” “budget,” and “progress” are key words connected to the Gordie Howe bridge project, but the most important word on the work site is “safety.”

“The Gordie Howe International Bridge project team emphasizes the importance of health and safety and employs extraordinary measures to ensure the well-being of workers and the public,” says a bridge official.

This is particularly meaningful after a worker on the Ambassador Bridge plummeted more than forty meters into the Detroit River last summer. Thank goodness, he survived. In a world abounding with guardrails, seatbelts, and bicycle helmets, that accident was a sobering reminder that working on the bridge structure is a dangerous endeavour.

When completed, the clear span of the Gordie Howe International Bridge will extend 2,798 feet (853 meters) making it the longest main span of any cable-stayed bridge in North America. The Ambassador Bridge extends 1,850 feet (563 meters) in length, making it the longest bridge in the world until the Golden Gate Bridge was completed in San Francisco in 1937.

The Gordie Howe International Bridge will not only provide a new crossing option for people and goods, but it will be a gem along the Windsor shoreline, bringing beauty to an area sorely in need of it. It will be a spectacle to behold each night: The majestic bridge towers will be illuminated by white LED lights. “Light spillage” will be limited by optics and shielding that will have the ability to adjust—as needed—to accommodate for such as fog, or peak migratory bird season. The bridge’s stay cables will be individually illuminated from the base upward with white, precision optic LED lights, positioned to allow the bridge towers to absorb the glare, further reducing light spill into the sky. The bridge deck will be lined linearly with white LED lights defining its edge from one end of the bridge to the other.

Beyond the new bridge’s aesthetics, it will be accessible not only to vehicle traffic, but also to cyclists and pedestrians by way of a multi-use path that will accommodate two-way traffic in either direction. Pedestrians and cyclists will be protected by concrete barriers separating vehicular traffic from people on foot or bikes, with dedicated processing areas at each Port of Entry to welcome them.

The Gordie Howe International Bridge team is working with the City of Detroit to create pedestrian and cycling connections into adjacent road and trail networks in the city, including the Southwest Detroit section of the Joe Louis Greenway. Users of the bridge’s multi-use path will access local street connections on West Jefferson Avenue, adjacent to Historic Fort Wayne. From there, users can travel along the new West Jefferson Avenue multi-use path to connect to new cycling infrastructure via Green Street or Campbell Street which leads to bike lanes on Fort Street. Additional bike lanes have been integrated into the new road crossing bridges at Springwells, Green, Livernois and Clark Streets to connect the communities on the north and south sides of I-75.

When the new bridge reaches completion and opens for use in 2025, Windsor-Essex will have yet another symbol of its industry and ingenuity, another towering statement that tells all who behold it: We build things here.