Mehari Hagos is keeping kids off the street one set of sneakers at a time

Growing up in Windsor’s Glengarry neighbourhood isn’t easy. For many teens, it means growing up too soon—forgotten children with a wretched destiny. Mehari Hagos is breaking the cycle with his program—MH100.

By 18 years old, Hagos knew this life all too well. As he walked into Windsor Jail, the skin on the back of his neck prickled—like someone had walked over his grave. He was there to see his brother in that ancient, soul-crushing home away from home. The trip to the big house was uncomfortable and claustrophobic, and as walked down its nondescript and bleak hallways, he saw something that numbed him to his core—two sections of Windsor Jail were packed with people from his neighbourhood.

Hagos, now 32 years old, immigrated from Eritrea with his mother at the age of six.

“When I was 11 years old, one of my best friends, he used to babysit for this lady. The lady was a notorious drug dealer in Windsor—well known to the police, well known to everybody,” explains Hagos. “She would basically groom young black men into selling crack cocaine. It started with my older brothers, my friend’s older brothers, their older cousins, and it just got to be generation after generation.”

“They’re grooming you—instead of playing basketball and sports, they’re grooming you to sell drugs.”

The residents of Glengarry neighbourhood had a tumultuous relationship with the Windsor Police. “They would raid your neighbour’s house and put a gun to your head as an 11-year-old or 12-year-old and get roughed up a bit,” recalls Hagos. “I experienced everything—police brutality, wrongful accusations.”

He remembers that, as a child, he wanted to be a firefighter. His dreams were dashed when a teacher, a white man in a position of authority, told him he could never be a firefighter because he was always late. What the teacher didn’t know was that the young Hagos was routinely awakened at night as the police raided various homes in the early morning. He had lost count of how many times he had to step over police tape on his way to school, and he often went to school hungry.

At 18, Hagos met former City of Windsor councillor and executive director of the Sandwich Teen Action Group, John Elliott, who encouraged him to be a helping force in his community. A year later, he took up a job at Windsor Water World where he met Bonnie Bailey—a person he credits with changing his life. She helped him form his program—Training with Mehari.

“Bonnie Bailey saw something in me that a lot of people didn’t,” states Mehari. “A lot of people thought I was going to follow my brother’s route—selling drugs and going to jail. Once I got that job, we started going door-to-door, me and Bonnie, and got these kids. All of these kids happened to be my nieces, nephews, cousins, friends—because this is my neighbourhood.”

Hagos’s program, MH100, is now a decade old. He teaches fitness, financial literacy, and female empowerment through his “Money Team”; helps provide employment; and pays for driver’s licence testing fees and post-secondary educational scholarships. The program has expanded across the city and has been a footprint for other cities as well, such as Toronto, Hamilton, and Ottawa. Hagos runs MH100 as an afterschool program and once completed, he rewards his participants with a new set of shoes.

“When I first came to Canada, I told my mom, ‘Hey man, I’m slipping everywhere. I need back-to-school shoes,’” he recalls. “She went to the States, bought me some shoes.” There was something not quite right about these shoes. “I was killing everybody on the grass, I was so fast, and when I went into the hallway, it was like ‘click-clack’ and my buddy says, ‘Hey MH, why do you got on baseball cleats?’” he chuckles. “So, my mom bought me baseball cleats for back-to-school shoes thinking in her head, ‘He’s never going to slip.’”

One day, a member of his youth program happened to walk in wearing baseball cleats and he was instantly taken back. It gave him an idea—MH Kicks for Kids.

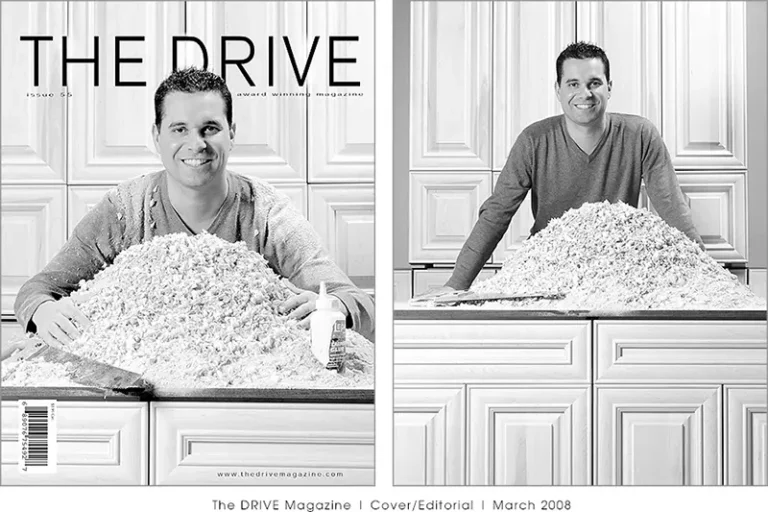

“When you do good in fitness or you do good in school, I buy you shoes,” explains Mehari. “I started with a couple pairs and the next thing I know, I bought over 5,000 pairs of shoes since my program started. This past Christmas, alone, it was my 10th anniversary and I bought over 60 pairs of shoes for all the kids in the neighbourhood.”

“All throughout the years, if you need shoes, I’ll buy you shoes—obviously, if you’re an athlete, you need basketball shoes, you need football cleats, baseball cleats—but during Christmas, I buy the whole neighbourhood shoes. In the summertime, if they complete the summer program, I also buy them shoes too.”

To the kids in his MH100 youth program, the gesture means everything. “When you’re from the ‘hood,’ a new pair of Jordans or Nikes is the world to you because your parents can’t afford that,” says Hagos.

MH100 has provided $1.6 million in scholarships to its kids and its student-athletes are also getting noticed by the NCAA and U Sports. “Kids from my neighbourhood, they don’t go to county jail no more, they get Division I athletic scholarships,” beams Hagos. “Just this year alone, we had nine kids get prep school and Division I scholarships.” In fact, two of the champion Carlton Raven’s starting five in U Sports basketball took part in the MH100 program.

He supports his youth group through MH100 Fitness, where he teaches boxing boot camps and one-on-one fitness training. Half of all proceeds go back into the MH100. Hagos fosters community connections between his kids and their benefactors and has gone to lengths to break the stigma between the Glengarry neighbourhood and the Windsor Police through outreach programs with MH100.

Hagos is also pushing his kids to explore the local post-secondary educational scene. “When I was 17, I didn’t even know where the University of Windsor was,” he states. “You never leave the neighbourhood because nobody in your family ever went to university. You know who the latest rapper is, you know the latest superstar athlete, but you didn’t know where UWindsor or St. Clair College was. We take trips to those schools and we’ve become cool with the athletic director, Mike Havey, at the university.

For years, MH100 has operated in the old Windsor Water World building. In 2015, when the City of Windsor was set to close the building, Hagos stepped in to put it to use. Despite being a non-for-profit and currently having an application to become an official charity, according to Hagos, MH100 does not get a reduced or subsidized rental fee on the building. In 2018, then–Minister of Child and Youth Services Michael Coteau reached out to Hagos and lined him up with a substantial grant. In turn, Hagos renovated Windsor Water World.

MH100’s benefits to the City of Windsor cannot be understated and Hagos is grateful for the support he has received from Mayor Drew Dilkins and councillors Rino Bortolin and Kieran McKenzie. “This is saving the City so much money because if the kids are working, they’re less likely to go on welfare. If they’re going on a scholarship to a university, they are less likely to commit crime, they’re less likely to go do drugs—which then, in the end, it saves the City of Windsor money,” he explains.

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the status quo for MH100. Due to restrictions, the kids lost access to their building and then the City repurposed their newly renovated site. “The City of Windsor took my community centre and my fitness centre and made it a homeless shelter,” frets Hagos. “Now, when you go to my community . . . a homeless person can come in and get refreshments, food, clothes, all those things, but a six-year-old black youth that lives in that neighbourhood was getting denied access.”

For the time being, MH100 has been moved to the John Atkinson Memorial Community Centre.

“A lot of people give us different accolades, the Government of Canada writing about us, and all of these things are great, but my best accolade is when ex–drug dealers and people who went through the system come to me and say to me, ‘Man, I wish you were around when I was a kid,’” says Hagos.

“They thank me so much because I’m able to save their son’s life, their daughter’s life because they’re in my program. I was able to break generational curses.”