Walter Riggi’s recording studio is a thing of beauty. Located in St. Clair Beach, his creative lair will force you to stop upon entering, gander, and double take in its immensity. Walls of amplifiers, organs, drums, Fenders, Gibsons, guitar pedals, equalizers, reel-to-reel recorders, and countless widgets and gadgets surround you, and at its heart, like a general’s bunker, a massive mixing table and sound booth.

Riggi, an award-winning Juno Awards judge, sound engineer, producer, video editor, and video colourist, explains that modern artists want an immersive experience, a wonderland of creative bounty, ripe for the picking.

“Nine times out of 10, they’re going to say that they want the experience,” he states. “Would you rather go to your neighbourhood park for free, or would you rather go to Disney World for $10,000? Well, I’m going to Disney if I’ve got $10,000.”

For forty years, Riggi has been in the business of making his clients sound good and look good. In 1982, as a 16-year-old keyboardist, his father purchased his first VCR/camera combo at Krazy Kelly’s – an acquisition that changed the trajectory of Riggi’s life.

“I fell in love with the process of filming video,” recalls Riggi. “We started doing weddings; then I got asked to do music videos because I was in my high school’s music department. Around that time, I went to do a demo at a demo studio, and I fell in love with that process too. So, I was all wrapped up in the media game. I was totally into recording things – whether it was visual or auditory.”

Growing up in the eclectic musical tapestry of the 1980s, Riggi’s ear for music benefited from radio’s varied music variety and fueled his love of keyboards. “I liked listening to ’80s pop music at the time, and I loved how diverse music was in the ’80s, where you could listen to rock and then right away you were listening to Duran Duran, then you went to Def Leppard.”

Having started with an 8-track reel-to-reel recorder, now, with four decades in the field, he has the distinction of having witnessed the digital revolution take hold.

“The 4-track exploded the home recording market,” states Riggi. “You used to book time at a studio for demos. When the 4-track came out, and the 8-track came out, it exploded the idea of homemade demos – and it’s the same thing today. You can still do that same concept, but if you want that extra polish, you either do the full experience in a studio like this, or you bring your tracks in and say, ‘Can you make it better?'”

“The goal was always to get to a studio that had tape because our heroes recorded on tape and that was the medium. Digital wasn’t really anything to record with. Artists were trying to, but it was George Lucas who started the whole push towards digital when he started digitizing Star Wars, and that was to help him edit and piece things together.”

Riggi says that digital audio didn’t reach the forefront of the industry until Avid Audio brought the revolutionary Pro Tools recording software to the market, which became popular in the mid to late 1990s. However, it took a while for digital to win over the audio recording industry.

“Digital was so slow, so difficult to get your head around and to try and make it sound right,” he explains. “You’d spend more time trying to record things into the computer, to make it sound decent, than hitting play and recording on tape.

“Anytime you slow down an artist in a studio, you become the bottleneck. The artist falls out of being creative. The mind starts to wander on girls, or homework, or their wife, or their job, touring, whatever it is, and it creates a bad experience in the studio.”

The creation of software plugins to help with sound editing almost killed the old analog market, but, in recent years, it has seen a resurgence with artists trying to create a more authentic “in the moment” sound. However, digital is still the way to go for capturing those sounds due to the speed at which they can be recalled for use.

“My studio is a true hybrid, whether it is the digital side or the analog side, that recall-ability is not a problem,” he says.

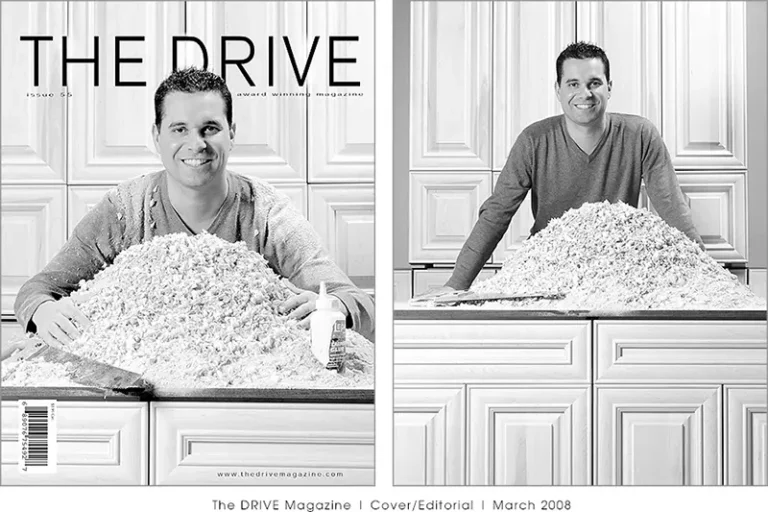

Riggi’s services have been sought after by many noted artists. Actor Brian George of Seinfeld and The Big Bang Theory fame filmed the pilot for a cooking show, Fear of Frying, with Riggi in a furniture store near Blenheim. He has also created the promo videos for three Miss Universe Canada winners, put together the soundtrack, foley, and sound effects for the award-winning short film Burden II, and recently finished colouring an upcoming Florida-based Christian television series for PureFlix.

When asked about some of his favourite music acts he’s worked with, Riggi instantly says Mike Sleath, the drummer of Shawn Mendes’ touring band.

“(Sleath’s) level of how he operates is a whole different thing,” explains Riggi. “Not a lot of flash, or the Neil Peart sort of thing, but when he’s locked down, he’s solid. His hits were methodical, and his explanation of how things work behind the stage was eye-opening.”

Riggi is also excited about his work with Windsor-based Pink Floyd tribute band J#Major. “They do a superb job and really pay attention to the details of Pink Floyd,” says Riggi. “Their album has 11 songs and has elements of Pink Floyd in it, and it’s not something you’d play on commercial radio. They put a lot of thought into chord structure, passages, and who should play where. It’s very well produced, and they spent time here to get what they wanted.”

Riggi says the key to creating a great song is recording the right song right. He says that classic songs like My Girl by The Temptations and Back in Black by AC/DC are instantly memorable. One way to create this is through a catchy hook. Also, the song needs to be recognizably from that artist. If the song is not sung in the right key, brand confusion can be a big problem if listeners cannot recognize the singer. Also, does the song escalate? Does it go from a simmer to a boil? Riggi says these elements can be created through good engineering, equipment selection, having a strategy, and extracting the right sound from the artist’s head.

“The engineer’s job is to serve, not take over,” he says. “The producer listens to what the band has done, understands their vision, and cleans it all up – the adult on the project.”

In recent years, the music scene in Windsor, once robust, has taken a hit. In reaction to this, Riggi and a friend, Rob Palombo, started the Raise Your Voice singing competition to highlight and celebrate local talent.

“Raise Your Voice was my rebellion against the local scene slowing down for bands and help artists try to come up with ways to get out there,” explains Riggi. “There used to be jam nights. On a Monday night, you used to go out, and you were a nobody, but you played. If you felt like you needed to freshen up your lineup as a band, you could go to these jam nights.

“When all of the raw, unheard, undiscovered talents dried up and stopped, this was a rebellion on my part and saying, ‘No, we need this. This is our future.'”

He says that the contest, which is now in its fifth season, has been highly successful, and many participants have gone on to perform in bands or get offered local venues to continue performing at.

Since 2017, Riggi has been honoured to participate as a judge and delegate with the Juno Awards. “That was through a mutual contact in Toronto,” he says. “It’s funny, the guy that had the final stamp of acceptance for me with the Juno Awards said, ‘Oh boy! You’ve been around this longer than I’ve been alive!'”

He says that it has been a privilege to help choose Canada’s top musical acts. As a judge, he helps narrow down who the final contestants for the awards are, while, as a delegate, he then helps select the eventual winner. He has the distinction of judging 15 categories, including Single of the Year, Album of the Year, Artist of the Year, and Group of the Year.

After four decades in the business, Riggi says what keeps his love of music going is the sheer range of it. He notes that one of the biggest pet peeves he’s encountered with artists is their insistence on using over-recycled classic songs – in particular, Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. “It’s been cut and changed so many times that it’s like, ‘I get it, just stop. Please!'”

However, what keeps him enamoured with the recording industry are the fresh voices, the new ideas, and the boundary-pushing of cutting-edge music and film.

“It’s never the same job twice,” says Riggi. “Whether it’s an artist that wants to come in and does country or rock, metal, pop, or synthpop, or just a guitar and singing, it’s a new thing. If it was always the same song, but just crafted for metal or crafted for pop, I think I’d lost my mind by now.”